By: Madeline Kaleel I’ve spoken on this blog before about executive functioning, or the mental processes that allow for the control of behavior. Executive functions encompass decision making and behavior regulation skills, and difficulty with these functions can inhibit your ability to set goals, organize, self-monitor, or regulate your emotions. So, when you notice that your child, or even you, are struggling with executive functioning, what can you do? That’s where the metacognitive process comes in. Metacognition, sometimes described as “thinking about thinking”, is the ability to step back and take a “bird’s eye view” of yourself and what you’re doing, developing self-awareness of what problem-solving strategies work for you, and which ones don’t. The metacognitive process, or cycle, involves three stages to coach you or your child through in order to improve their self-awareness and ultimately their executive functioning: Self-Monitoring, Self-Evaluating, and Self-Regulation. To walk through what this cycle looks like, let’s consider the case of Ashley. Ashley is a new sixth-grade student that has been struggling with keeping up to date on her math homework. She often doesn’t turn assignments in, and when she does, they’re usually incomplete. How can we use the metacognitive cycle to help her? Self-Monitoring is referred to as the observing stage, where you ask yourself “what am I doing?”. Taking a step back, you look at the strategies you’re trying to use, how you’re going to use it, and you make sure you’re following the plan. In Ashley’s case, she uses an academic planner in order to keep up with her homework. She writes down her assignments and tries to remember to check it daily to make sure everything has been completed. Self-Evaluating is the judging stage, where you ask yourself “how am I doing?”. After utilizing a strategy or technique for some time, you look at your performance and outcomes and judge how well it worked. This could be as specific as looking at a grade for a specific assignment, or as broad as your grade for the semester. For Ashley, she looked at her math grade and realized she was not doing well. Even using the planner, most of her assignments are still missing, and her overall math grade is suffering as a result. Self-Regulating is the modifying stage, where you ask yourself “what do I need to change?”. If you had poor outcomes during the self-evaluating stage, this is where you change your strategy to something more effective. Sometimes that means the strategy didn’t fit well with the environment, the task, or the person using it. However, you could also discover that your strategy resulted in increased performance and no change is necessary. Ashley reflected on different ways of tracking her homework, and decided to try using her Google calendar instead, as well as set reminders specifically for her math homework. After the self-regulating phase, the cycle continues back to self-monitoring. By coaching your child through these steps, you ultimately increase their self-awareness and metacognition skills to a point where, in the future, they can coach themselves through the cycle. If you’re wondering how coaching them through the cycle works, check out Peg Dawson and Richard Guare’s books Executive Skills in Children and Adolescents: A Practical Guide to Assessment and Intervention and Coaching Students with Executive Skills Deficits.

1 Comment

By: Madeline Kaleel Sometimes referred to as cognitive controls, executive functions are mental processes that allow for the control of behavior. These controls range from basic to higher order, with higher order executive functioning requiring the use of two or more of the basic skills. Basic executive functions include attentional control (concentration), inhibitory control (self-control), working memory, and cognitive flexibility. Higher order executive functions, such as planning, organization, and fluid intelligence, require an individual to use multiple basic executive functions simultaneously. Sometimes described as “the CEO of the brain”, these functions allow us to set goals, organize, self-monitor, and overall get things done. We aren’t born with these abilities, however. Executive functions are something that gradually develop and change over time, and they can be improved on at any point in your life. While growth in these areas typically comes about naturally through aging and experience, those with executive functioning issues may find one or more of these basic functions challenging. Executive functioning issues are not a diagnosis in and of itself, but it’s a common problem for those diagnosed with ADHD, a specific learning disability, or other learning and attention issues. So how can I tell if my child is struggling with executive functioning? Executive functioning issues present themselves different in each person. Kids may struggle with only one or two of the functions, while others may find all areas difficult. Similarly, different issues will present themselves at different points in life; the functions that a kid in elementary school struggles with are different than ones a high-schooler. Here are some possible signs that kids struggling with executive functioning may present:

My child shows one or more of these signs, how can I help? There are countless online resources and activities that you can use to help your child improve their executive functioning skills and succeed in life and school. It’s important to work with your child and learn which areas they need to focus on and what best helps them. If your child needs extra help, it could be beneficial to enroll them in courses or psycho-educational group to get more in-depth training and attention.  By Karen Gniadek, PLPC I clearly remember the day my daughter came home from school with a letter informing me that she had qualified for reading intervention. I was shocked and felt like a failure as a mother. After all, I was a stay-at-home mom and former special education teacher. I thought I had done everything right to set her up for success: I read to her from before birth on, took her on weekly trips to the library, exposed her educationally enriching experiences, and fostered her interests. How could this be happening?! After only the first semester of first grade in reading intervention, my daughter’s teacher assured me that she had caught up and was working on grade level. And she did remain near grade level reading throughout school, yet I knew there were areas in which she was still struggling, including: memorizing math facts; spelling, reading out loud, test anxiety, and memorizing facts associated with history or science. I will admit that I often lacked compassion when working with her at home. I wanted to be patient and supportive, but was frustrated when couldn’t she recognize that a word she read two sentences before was the same word she was seeing now or that 6 x 8 = 48 (for goodness sake it rhymes). FYI - rhyming is something that dyslexics often struggle with. The answer lies in dyslexia. The truth is that many parents and children do not realize that it is impacting them. Oftentimes, people develop compensatory skills which hide their weaknesses. Dyslexia is defined as a learning disability in reading that is neurobiological in origin and affects phonetic (letter sound) recognition, word decoding, and spelling. In short, students will be disfluent readers who have difficulty applying the strategies necessary to sound out words. There is much more to dyslexia, but I will go into this more in another blog. It is estimated that 20% of the overall population has dyslexia at some level. Like most brain differences, the severity of dyslexia symptoms spans a continuum from mild to severe. Those most severely impacted are often identified in school and helped via the IEP or 504 process. Those moderately to mildly impacted oftentimes go undiagnosed and unserved. It is these students for whom the new Missouri dyslexia law hopes to help. The law went into effect this school year, 2018-2019. It has three major components. The first component requires districts to screen all students in grades kindergarten through three for dyslexia. Students who via the screening are found to have delays in reading possibly related to dyslexia will be monitored for reading growth and should receive “reasonable accommodations” in the classroom. The final component mandates that all teachers receive two hours of professional development about dyslexia. Notably missing from the law is a requirement for schools to offer specific dyslexia reading interventions. With that said, the final recommendations of the task force tasked with developing recommendations on how districts should implement this law put forth numerous recommendations on the best types of instruction to remediate those students fitting a dyslexic profile. The final recommendations of this task force were completed in October 2017 and can be found on Missouri’s Department of Elementary and Secondary Education’s website. Districts have the freedom to choose which screening devices to use, who should screen the students, and how to accommodate and/or remediate students flagged as demonstrating characteristics of a reader struggling due to dyslexia. What, then, is a parent or caregiver to do?

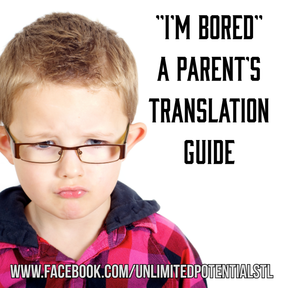

Karen Gniadek is under the clinical supervision of Andrea Schramm, LPC (MO #2013041567)  By Caitlin Winkler, PLPC Backpack, check. School supply list, check. New clothes, check. Haircut, check. It’s that time of year. Saying good-bye to summer and hello to school is getting closer, if not already here, and you’ve checked (or almost checked) all the boxes on your to-do list. Each year we do our best to prepare our child for a new school year. Something we often fail to discuss is the need to be mentally and emotionally ready as well. School brings a whole new set of trials each year. From academic challenges, teacher meetings, to tears over friendships, missing the bus, and the excitement of starting something new, this school year is bound to have its ups and downs. How can you help get ready for those tough times? Five Tips to Prepare Mentally and Emotionally for the New School Year: 1. Meet physical needs first. If you can remember Maslow’s hierarchy of needs from Psychology class, basic physical needs are the foundation upon which everything else is built. It is hard to get up for the bus, be prepared for a test, and meet obligations at school if you’re not sleeping well, not getting adequate nutrition, and do not have a secure and safe place to live. 2. Talk to your child about their thoughts and feelings. You could ask: What are you looking forward to? What are you nervous about? What are you excited to learn? Who are you looking forward to meeting? What are some concerns you have? How will this year be different than last year? Your child may surprise you with his or her answers. Validate their feelings and listen to their concerns without passing judgment or minimizing their thoughts. It is important for them to feel heard and understood. 3. Be aware of your child's struggles. Does your child have test anxiety? Is making new friends scary or really hard? Does your child struggle with having positive behaviors at school? Think about your child's strengths and weaknesses. As parents, it can be easy to only want to see the great things about our child, but the reality is, our children are not perfect. Everyone struggles with something. Helping your child prepare, work through, and persevere through a challenge or limitation is so important. Connecting your child to resources, such as tutoring, social skills groups, and counseling can make a huge difference. Be proactive in reaching out for help. 4. Give them the power. Many people pass blame and fault to others. Even as adults, we do this. But, something so vital for our children to learn is the fact, "I can control myself- my behaviors, my thoughts, my attitude, my words." They have the power to control themselves and are ultimately responsible and accountable for their actions. Once they recognize and learn this, they can tackle any challenge thrown their way. They can handle a tough teacher, an argument with a friend, a low grade on an assignment, or not making the team. As children and as adults, we choose our thoughts, whether they are positive or negative, and our actions are born from those thoughts. Positive thinking leads to positive feelings and positive behaviors. 5. Prioritize your schedule. We often expect ourselves and our children to keep up a crazy, fast-paced schedule. Many children are exhausted not just physically, but mentally and emotionally as well from the demands on our calendars. Cutting back on sports practices, extracurricular activities, and outside commitments may be necessary. Our children need time to just be kids- time without structure, time-lines, and expectations placed on them. Make time to play outside, laugh as a family, and have a night at home. This can make a huge difference in the mental and emotional well-being of your child. Caitlin Winkler is a Provisionally Licensed Professional Counselor at Unlimited Potential Counseling & Education Center in O'Fallon. Caitlin is under the clinical supervision of Emily Kircher-Morris, LPC (MO #2012026754).  By Emily Kircher-Morris, LPC If I had a dime for every time a child or student told me that they were bored or that something was boring, I'd have enough money for a boring trip to Mexico with my husband. (Wouldn't boring be absolutely wonderful? When did my life go from abhorring boredom to it becoming a life goal? Anyway, I digress...) What I've found through many conversations with children, teens, and parents is that the phrase "I'm bored," or, "This is boring," often doesn't mean what it seems. Here is a handy guide for parents and teachers to understand the possible alternative meanings to complaints of boredom. "I don't have anything to do." Self-regulation is an executive functioning skill and this skill develops based on a child's maturity level. A child may have a million toys, a trillion games, and three-quarters of a ton of arts and crafts supplies. But, thinking about available options, prioritizing which seems the most interesting, and initiating the task are directly related to executive functioning skills and a child may need some ways to help figure out what they want to do. Creating a "menu" of options from which a child can choose or creating a "grab bag" with ideas of activities listed on individual pieces of paper can help take the decision-making out of the choice. "This isn't fun." Helping to clean the house typically isn't exactly a thrill a minute. However, if a child is busy and engaged, they aren't typically "bored." When a child complains of boredom in a school setting because a task isn't fun, parents may misinterpret it as the child saying they aren't challenged. Unfortunately, some academic tasks simply aren't all that fun, no matter what the teacher tries. Perseverance through a task that isn't fun but is necessary isn't easy for adults; helping children focus on the benefits of the outcome and monitoring their progress can help them to build this skill. "This isn't challenging enough." When a child fails to complete schoolwork and complains of being bored in class, it is possible that the work isn't challenging enough. (I should note, though, that many times the complaint is more closely related to one of the two reasons listed above.) This can go in two different directions: In one situation, the child begins acting out and getting in trouble. In the second situation, the child politely sits and completes work, compliant, bored, and not learning. Advocating for your child with the teacher for appropriate work is a necessary step for parents to take if this is the case. "This is too hard." The flip side of not being challenging enough is when a child finds a task too difficult. Sometimes a child doesn't even realize that they don't understand; they just know they don't want to attempt the task. When investigating the root cause of the "I'm bored" refrain, ask the child to restate to the task they are supposed to complete. If they are unable to explain, further instruction, modified requirements, or other accommodations may be appropriate. "I'm lonely." Parenting the child who needs to be with people can be exhausting. Suggestion after suggestion of activity may fall flat if a child is complaining of boredom because they are simply lonely. Recognize the child's need and dedicate time to "fill their bucket" with undivided attention. Negotiate with siblings who may prefer more alone time to engage with the brother or sister who thrives on attention. "I'm generally unhappy and don't know how to fix it." Sometimes kids just aren't happy. They often lack the emotional vocabulary to share how they are really feeling. Perhaps they are feeling worried, defeated, or excluded. "I'm bored" becomes a catchall for these uncomfortable feelings. Digging deeper to see what other emotions are beneath the boredom is key. It is also important to note that children and teens can be susceptible to depression and a child who is frequently uninterested in activities that at one time were engaging can be a warning sign that the child is depressed. "Nothing seems interesting." And finally, when all other options are exhausted, boredom may just be boredeom. Although there are options, none of them seem enticing. My Aunt Francine use to tell us, with unimpressed frankness, "You're not bored; you're boring." The lesson she was hoping to teach is that boredom is easily vanquished with a little creativity and imagination. Teaching kids ways to play with situations in their minds and amuse themselves in boring situations is an excellent skill to learn. |

Archives

August 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed