|

By Beth Cieslak, PLPC

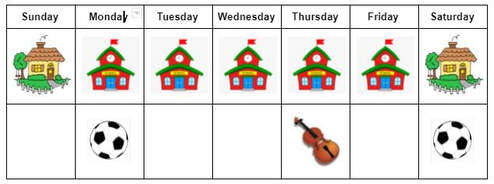

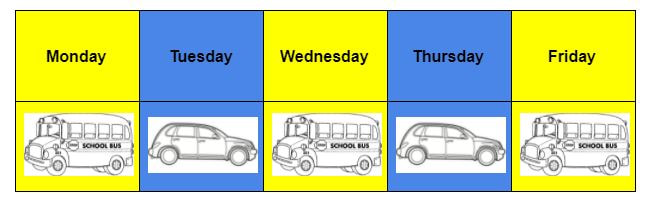

New schedules and routines can be exciting, but also come with a variety of mixed emotions for all ages. We may be excited about a new opportunity, but also unsure and anxious about the unknown aspects. As adults, we utilize calendars, phone reminders, and sticky notes to keep track of the many things going on in our lives. Kids and teens also benefit from these supportive strategies. Visual schedules consisting of pictures and/or simple words are effective tools to meet this need. Visual schedules help to increase confidence and minimize anxiety. Compliance resistance, power struggles, and prompt dependency may also decrease with the use of visual supports. Sheri Klugmann, Ramapo for Children Senior Parent Educator, explained that visuals help children to:

Including children and teens in the planning and preparation of visual schedules builds ownership of ideas and promotes success. What aspects of the day/week are creating the most stress or uncertainty? Would you like to write or draw pictures to illustrate? Can we take photos of the places in our routine, such as home, school, activities? Tech savvy families may enjoy creating visuals utilizing online image searches. Accessibility to these visual supports is essential. Post visual schedules where they are easily seen, such as on the refrigerator or bedroom wall. Place an additional schedule inside their backpack for access away from home. Teens may prefer to create and access visual schedules on technology devices such as a cell phone. Next comes teaching and practicing use of the visual schedule. Assist the child/teen in referring to the schedule for information. Some visuals will require identification of the place they are at on the schedule. Small binder clips or clothespins work well for pointing to a specific area. Another idea is to mark off completed tasks or days in the schedule. Here are some examples of visual schedules to get you started. I wish you and your family the very best as we embark on the new school year! Beth Cieslak, PLPC is under the clinical supervision of Pam Lueders, LPC (MO#2015026733)

0 Comments

By: Madeline Kaleel I’ve spoken on this blog before about executive functioning, or the mental processes that allow for the control of behavior. Executive functions encompass decision making and behavior regulation skills, and difficulty with these functions can inhibit your ability to set goals, organize, self-monitor, or regulate your emotions. So, when you notice that your child, or even you, are struggling with executive functioning, what can you do? That’s where the metacognitive process comes in. Metacognition, sometimes described as “thinking about thinking”, is the ability to step back and take a “bird’s eye view” of yourself and what you’re doing, developing self-awareness of what problem-solving strategies work for you, and which ones don’t. The metacognitive process, or cycle, involves three stages to coach you or your child through in order to improve their self-awareness and ultimately their executive functioning: Self-Monitoring, Self-Evaluating, and Self-Regulation. To walk through what this cycle looks like, let’s consider the case of Ashley. Ashley is a new sixth-grade student that has been struggling with keeping up to date on her math homework. She often doesn’t turn assignments in, and when she does, they’re usually incomplete. How can we use the metacognitive cycle to help her? Self-Monitoring is referred to as the observing stage, where you ask yourself “what am I doing?”. Taking a step back, you look at the strategies you’re trying to use, how you’re going to use it, and you make sure you’re following the plan. In Ashley’s case, she uses an academic planner in order to keep up with her homework. She writes down her assignments and tries to remember to check it daily to make sure everything has been completed. Self-Evaluating is the judging stage, where you ask yourself “how am I doing?”. After utilizing a strategy or technique for some time, you look at your performance and outcomes and judge how well it worked. This could be as specific as looking at a grade for a specific assignment, or as broad as your grade for the semester. For Ashley, she looked at her math grade and realized she was not doing well. Even using the planner, most of her assignments are still missing, and her overall math grade is suffering as a result. Self-Regulating is the modifying stage, where you ask yourself “what do I need to change?”. If you had poor outcomes during the self-evaluating stage, this is where you change your strategy to something more effective. Sometimes that means the strategy didn’t fit well with the environment, the task, or the person using it. However, you could also discover that your strategy resulted in increased performance and no change is necessary. Ashley reflected on different ways of tracking her homework, and decided to try using her Google calendar instead, as well as set reminders specifically for her math homework. After the self-regulating phase, the cycle continues back to self-monitoring. By coaching your child through these steps, you ultimately increase their self-awareness and metacognition skills to a point where, in the future, they can coach themselves through the cycle. If you’re wondering how coaching them through the cycle works, check out Peg Dawson and Richard Guare’s books Executive Skills in Children and Adolescents: A Practical Guide to Assessment and Intervention and Coaching Students with Executive Skills Deficits.  By: Madeline Kaleel Sometimes referred to as cognitive controls, executive functions are mental processes that allow for the control of behavior. These controls range from basic to higher order, with higher order executive functioning requiring the use of two or more of the basic skills. Basic executive functions include attentional control (concentration), inhibitory control (self-control), working memory, and cognitive flexibility. Higher order executive functions, such as planning, organization, and fluid intelligence, require an individual to use multiple basic executive functions simultaneously. Sometimes described as “the CEO of the brain”, these functions allow us to set goals, organize, self-monitor, and overall get things done. We aren’t born with these abilities, however. Executive functions are something that gradually develop and change over time, and they can be improved on at any point in your life. While growth in these areas typically comes about naturally through aging and experience, those with executive functioning issues may find one or more of these basic functions challenging. Executive functioning issues are not a diagnosis in and of itself, but it’s a common problem for those diagnosed with ADHD, a specific learning disability, or other learning and attention issues. So how can I tell if my child is struggling with executive functioning? Executive functioning issues present themselves different in each person. Kids may struggle with only one or two of the functions, while others may find all areas difficult. Similarly, different issues will present themselves at different points in life; the functions that a kid in elementary school struggles with are different than ones a high-schooler. Here are some possible signs that kids struggling with executive functioning may present:

My child shows one or more of these signs, how can I help? There are countless online resources and activities that you can use to help your child improve their executive functioning skills and succeed in life and school. It’s important to work with your child and learn which areas they need to focus on and what best helps them. If your child needs extra help, it could be beneficial to enroll them in courses or psycho-educational group to get more in-depth training and attention.  By Emily Kircher-Morris, LPC A child keeps kicking his brother's car seat, even after his mom has asked him to stop. The class clown keeps interrupting the teacher with off-topic and mildly inappropriate comments. A preteen girl crumples her homework and dramatically hides her face in her arms on her desk. A young boy has a meltdown because he is told they are having cookies instead of ice cream for dessert. When trying to figure out what is behind these problematic behaviors, parents and teachers may come to the conclusion the child is engaged in negative attention-seeking. They come to the conclusion that the best response is to ignore or give a negative consequence for the behavior. Many people feel that attention-seeking behavior is a negative trait. The attention the child is seeking is unearned and the result of a child being overly emotional and dramatic. The reaction may be to ignore the behavior or even give a negative consequence to the child. I'd like to suggest a different way to look at attention-seeking behavior. If we consider all behavior to be communication and ask ourselves, "What is the child needing from this interaction?" we may find some ideas of how to handle the behavior. Let's reframe attention-seeking as reassurance-seeking. Their behavior is saying: Am I alone? Do you love me? Am I worthwhile? Even if I act this way, will you stick with me? We all need attention once in a while. We may seek it in positive ways, through accomplishments and helping others. The reassurance we get from those acknowledging us can keep us going. Sometimes kids don't have the language or emotional regulation skills to get their needs met in the most convenient way for us. But, when we remind ourselves the attention-seeking is really reassurance-seeking, we build our relationship with the child and can help them learn more appropriate ways to seek that reassurance from us in the future.  By Karen Gniadek, PLPC I clearly remember the day my daughter came home from school with a letter informing me that she had qualified for reading intervention. I was shocked and felt like a failure as a mother. After all, I was a stay-at-home mom and former special education teacher. I thought I had done everything right to set her up for success: I read to her from before birth on, took her on weekly trips to the library, exposed her educationally enriching experiences, and fostered her interests. How could this be happening?! After only the first semester of first grade in reading intervention, my daughter’s teacher assured me that she had caught up and was working on grade level. And she did remain near grade level reading throughout school, yet I knew there were areas in which she was still struggling, including: memorizing math facts; spelling, reading out loud, test anxiety, and memorizing facts associated with history or science. I will admit that I often lacked compassion when working with her at home. I wanted to be patient and supportive, but was frustrated when couldn’t she recognize that a word she read two sentences before was the same word she was seeing now or that 6 x 8 = 48 (for goodness sake it rhymes). FYI - rhyming is something that dyslexics often struggle with. The answer lies in dyslexia. The truth is that many parents and children do not realize that it is impacting them. Oftentimes, people develop compensatory skills which hide their weaknesses. Dyslexia is defined as a learning disability in reading that is neurobiological in origin and affects phonetic (letter sound) recognition, word decoding, and spelling. In short, students will be disfluent readers who have difficulty applying the strategies necessary to sound out words. There is much more to dyslexia, but I will go into this more in another blog. It is estimated that 20% of the overall population has dyslexia at some level. Like most brain differences, the severity of dyslexia symptoms spans a continuum from mild to severe. Those most severely impacted are often identified in school and helped via the IEP or 504 process. Those moderately to mildly impacted oftentimes go undiagnosed and unserved. It is these students for whom the new Missouri dyslexia law hopes to help. The law went into effect this school year, 2018-2019. It has three major components. The first component requires districts to screen all students in grades kindergarten through three for dyslexia. Students who via the screening are found to have delays in reading possibly related to dyslexia will be monitored for reading growth and should receive “reasonable accommodations” in the classroom. The final component mandates that all teachers receive two hours of professional development about dyslexia. Notably missing from the law is a requirement for schools to offer specific dyslexia reading interventions. With that said, the final recommendations of the task force tasked with developing recommendations on how districts should implement this law put forth numerous recommendations on the best types of instruction to remediate those students fitting a dyslexic profile. The final recommendations of this task force were completed in October 2017 and can be found on Missouri’s Department of Elementary and Secondary Education’s website. Districts have the freedom to choose which screening devices to use, who should screen the students, and how to accommodate and/or remediate students flagged as demonstrating characteristics of a reader struggling due to dyslexia. What, then, is a parent or caregiver to do?

Karen Gniadek is under the clinical supervision of Andrea Schramm, LPC (MO #2013041567)  By Emily Kircher-Morris, LPC Because I work with many high-ability, gifted, and twice-exceptional individuals in my practice, I've noticed an interesting pattern with some of my clients. The story follows a specific path: A bright child was diagnosed with ADHD at a young age. Medication after medication had minimal benefit; often the parents abandoned medication altogether. As the child gets older, their lagging social skills cause more and more problems with friends and at school. We finally determine the appropriate diagnosis of Asperger's Disorder has been missed. Many children compensate well for social struggles and concerns may go unnoticed by parents and educators. If the child is gifted, asynchronous development explains many of the quirks the child may show. However, one would expect that as the bright, quirky, asynchronous child grows older, some skills (such as the ability to meet typical social expectations) would balance out. However, the DSM-V says that for a diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder, symptoms may not fully manifest until social demands exceed the abilities of the individual. When a child's struggles increase with age instead of balancing out, a diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)/Asperger's should be considered. So, why are these kids given an ADHD diagnosis instead of ASD? A close look at the symptoms of ADHD through the lens of Asperger's can help understand how this misdiagnosis can be made:

Parents, educators, and medical/mental health professionals need to be aware of the overlap of behaviors between these two diagnoses. If medications don't seem to make a difference for ADHD, it may be beneficial to consider the presence of ASD. If social skills seem to be regressing as a child enters late elementary, middle, or high school instead of balancing out, taking a look for Asperger's could help. And finally, considering each of the behaviors that was originally explained by ADHD, and whether the motivation for the behavior is better explained by traits of ASD, can help find an accurate diagnosis. While any mental health diagnosis for a child can be overwhelming, accurately identifying the cause of problematic behaviors allows for proactive interventions to be implemented earlier and with better efficacy.

By Emily Kircher-Morris, LPC

'Tis the season to rack your brain for gift ideas for some of those hard-to-buy-for family and friends. One of the hardest among these is your child's teacher. As parents, we don't really always know the teachers personally enough to get them something they really want. So goes the annual search for a gift that is unique (yet general enough that any teacher would like it) and in the right price range (somewhere between $5 Starbucks gift card and a full spa day). I used to be a teacher and a school counselor. Gift cards are always easy and appreciated but sometimes feel impersonal. Snacks are hard because some teachers don't eat gluten or sugar or coffee or chocolate (What????). Knick knacks and ornaments are tough because, eventually, there just isn't enough space to keep them. So - don't spill the beans to my kids' teachers yet - but here is what they are getting for Christmas this year: I'm giving each of them a gift basket filled with fidgets for their classrooms. Research is showing that more and more students learn better when their psychomotor needs are met. Especially for children with ADHD and other sensory needs, a small, unobtrusive fidget actually can help them focus better than without because it stimulates the small portion of the brain that needs a distraction so the other 95% of the brain can focus on the lesson. Adults need this, too; when I provide professional development, I bring baskets of fidgets, Play-Doh, markers, and candy to fill that sensorimotor need. Now, don't worry. I'm not going to stockpile my child's classroom with a full set of fidget spinners. (I know teachers who've had nightmares about out-of-control fidget spinner mutinies in their classrooms!) When I *teach* kids how to use fidgets appropriately (yes, kids need to be taught how to use fidgets to improve their focus), we have a few rules. The fidget cannot distract others, either visually or by making noise, and the person using the fidget needs to be able to maintain eye contact with the person who is speaking or teaching the lesson. Here are some of my favorite fidgets that I'll be giving my kids' teachers this holiday season. I've bought and tried all of these items and have them at my home and office.

These little tangles are a classic fidget that kids love. They twist and coil and wrap. The one downside is that some kids like to pull them apart and put them back together, which can be distracting in the classroom.

This is perfect for those kids who are always tipping their chairs. Simply wrap this exercise style band around the bottom two legs of a classroom chair for kids to use for counter pressure for their legs. Bonus: It won't result in falling over backwards!

Fun little fidget rings roll up and down a thumb or finger with minimal distraction or noise. They provide some pressure - kind of like a little massage for your finger!

File this under "Why Didn't I Think of That?" This little mesh tube that kind of looks like a little Chinese finger trap has a marble trapped inside. Squeeze the marble back and forth to engage kids without distracting others.

Another style of fidget ring, instead of rolling vertically on the finger, it rolls around the finger. The smooth roll this fidget provides is surprisingly calming and satisfying. Again, it is small and won't be distracting to other kids!

Another great option for the child who has a hard time staying still in his or her seat. These wobble seats take just enough effort for kids to stay stabilized so their wiggling isn't a distraction to themselves or others.

(BTW - These are Amazon Affiliate links. If you opt to purchase through this link, a small portion of your purchase price will be donated to the Gifted Support Network 501(c)(3) nonprofit in St. Charles, MO.)

For example, my son refused to wear a bike helmet more than once. Instead of taking his bike away, he had to research and find information about the risks associated with bike helmet safety and regulations. It was time consuming. I had to help him through the process. It also kept him from his preferred activities, but, it was engaging. It allowed him to create new connections in his awareness of the topic. It was much more effective than me lecturing him, too. And when he was able to share his learning, he felt proud of his work instead of ashamed of his mistake.

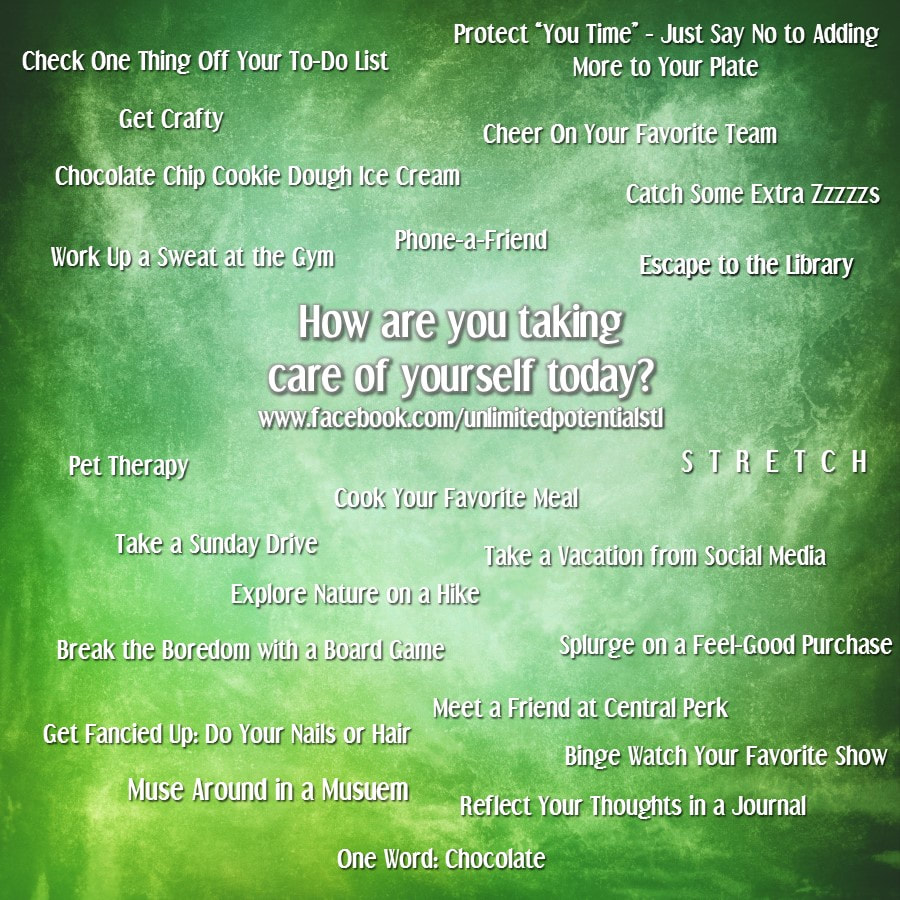

The downside of restorative consequences it takes effort, time, and creativity on the part of the parent. However, the long-term benefit in learning and the relationship it fosters between you and your child will be worth the effort. By Heather Kuehnl, PLPC Self-care is one of the most important things you can do for yourself. It can help decrease symptoms of anxiety, depression, and daily life stresses, as well as improve mood and overall health and well-being. When you take care of yourself, you are better equipped to care for those around you, as well. Self-care is also vitally important to children and adolescents as well. They can experience a myriad of moods, feelings, and mental health concerns. It is imperative that they are aware of, and supported with, ways to implement self-care strategies to help them manage every day stressors, symptoms of a mental health disorder, or simply get some of their wiggles out. Below you will find some great self-care activities, for children/adolescents and adults, to support you and/or your child with self-care. Heather Kuehnl, PLPC is under the supervision of Emily Kircher-Morris, LPC (MO #2012026754).

By Caitlin Winkler, PLPC Backpack, check. School supply list, check. New clothes, check. Haircut, check. It’s that time of year. Saying good-bye to summer and hello to school is getting closer, if not already here, and you’ve checked (or almost checked) all the boxes on your to-do list. Each year we do our best to prepare our child for a new school year. Something we often fail to discuss is the need to be mentally and emotionally ready as well. School brings a whole new set of trials each year. From academic challenges, teacher meetings, to tears over friendships, missing the bus, and the excitement of starting something new, this school year is bound to have its ups and downs. How can you help get ready for those tough times? Five Tips to Prepare Mentally and Emotionally for the New School Year: 1. Meet physical needs first. If you can remember Maslow’s hierarchy of needs from Psychology class, basic physical needs are the foundation upon which everything else is built. It is hard to get up for the bus, be prepared for a test, and meet obligations at school if you’re not sleeping well, not getting adequate nutrition, and do not have a secure and safe place to live. 2. Talk to your child about their thoughts and feelings. You could ask: What are you looking forward to? What are you nervous about? What are you excited to learn? Who are you looking forward to meeting? What are some concerns you have? How will this year be different than last year? Your child may surprise you with his or her answers. Validate their feelings and listen to their concerns without passing judgment or minimizing their thoughts. It is important for them to feel heard and understood. 3. Be aware of your child's struggles. Does your child have test anxiety? Is making new friends scary or really hard? Does your child struggle with having positive behaviors at school? Think about your child's strengths and weaknesses. As parents, it can be easy to only want to see the great things about our child, but the reality is, our children are not perfect. Everyone struggles with something. Helping your child prepare, work through, and persevere through a challenge or limitation is so important. Connecting your child to resources, such as tutoring, social skills groups, and counseling can make a huge difference. Be proactive in reaching out for help. 4. Give them the power. Many people pass blame and fault to others. Even as adults, we do this. But, something so vital for our children to learn is the fact, "I can control myself- my behaviors, my thoughts, my attitude, my words." They have the power to control themselves and are ultimately responsible and accountable for their actions. Once they recognize and learn this, they can tackle any challenge thrown their way. They can handle a tough teacher, an argument with a friend, a low grade on an assignment, or not making the team. As children and as adults, we choose our thoughts, whether they are positive or negative, and our actions are born from those thoughts. Positive thinking leads to positive feelings and positive behaviors. 5. Prioritize your schedule. We often expect ourselves and our children to keep up a crazy, fast-paced schedule. Many children are exhausted not just physically, but mentally and emotionally as well from the demands on our calendars. Cutting back on sports practices, extracurricular activities, and outside commitments may be necessary. Our children need time to just be kids- time without structure, time-lines, and expectations placed on them. Make time to play outside, laugh as a family, and have a night at home. This can make a huge difference in the mental and emotional well-being of your child. Caitlin Winkler is a Provisionally Licensed Professional Counselor at Unlimited Potential Counseling & Education Center in O'Fallon. Caitlin is under the clinical supervision of Emily Kircher-Morris, LPC (MO #2012026754). |

Archives

August 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed